With The Hunger Games series exploding in popularity and the first of the films based on Susan Collins’ trilogy being a huge box office success, I thought I’d take a look back to the past.

To see how Gladiators really were, how they were done in fiction before this and one particular story following in the series wake that has earned particular online ire. Because when we get down to it, the actual history of the gladiator games is something most people, even the writers of the most popular stories using it, do not know all the details.

That knowledge changes how the stories based on them are accepted.

Sadly, the more you know, the harder some are to accept.

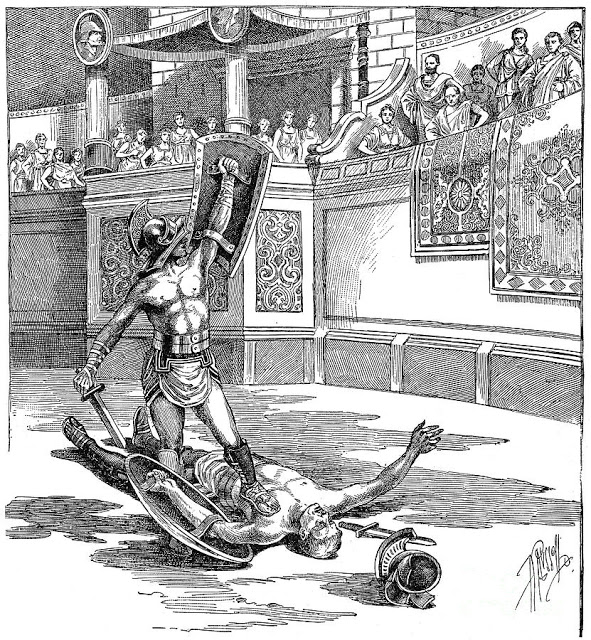

When the word ‘Gladiator‘ is mentioned , images of ancient Roman warriors battling it out in the sands of the Coliseum, trying their best to hack each other to pieces for the braying, bloodthirsty crowd dance in the mind, and before the final blow was struck, the audience always gave a thumbs down to the loser, signaling their demise.

This image is not quite accurate to what actually occurred.

For one, the Coliseum at the time was known as the Flavian Amphitheater. Most games were held in Amphitheaters. It only got the name Coliseum after a nearby giant statue was erected nearby, which was melted down hundreds of years ago to make cannons. The statue has long since been melted down and turned into cannons, but the name stuck.

For one, the Coliseum at the time was known as the Flavian Amphitheater. Most games were held in Amphitheaters. It only got the name Coliseum after a nearby giant statue was erected nearby, which was melted down hundreds of years ago to make cannons. The statue has long since been melted down and turned into cannons, but the name stuck.

The popular image of the gladiator is similarly skewered. Not even the movies set in gladiatorial times get these details right.

Of the ones I’ve seen, oddly, Spartacus comes closest to most of the aspects of the games.

Even with the oodles of research Gladiator did and the wonderful details it included, it still fell short of what occurred within the amphitheater and did not capture the mindset of Ancient Rome the same way as Spartacus.

To understand the games, we need to know several things. We need to understand what the games were and their logistics; we need to understand who the gladiators actually were; the audience’s mindset and the politics around them games; and finally, how they came to an end.

The Logistics

A typical day at the Amphitheater was a very long one and really was a full day event. The first part of the games was a natural history show, believe it or not. Exotic animals were brought in from the furthest reaches of the empire. Elaborate sets would be raised by stage hand hidden backstage and within, the animals were allowed to roam freely—predators and prey—until it came time for them to be killed. Some specially trained slave gladiators (Beastiari) were employed for this, either to kill the animals outright or to hunt them for public spectacle. In mid-day, things got gorier. That was when public executions occurred. Most high ranking Romans did not stick around for this, or at least made gestures towards disliking it—saying they were rather boring, vulgar or disgusting.

Romans were very creative in how they executed people and made sure it was not pleasant. Some were set upon by wild beasts; others were forced to kill each other in fights. But these criminals and outcasts (IE: Christians and other political dissidents) were not true gladiators. They had no training and were there just do die as part of their sentence. From 1:30 to 7:30, that is when the Gladiators fought. But these were not quick endeavors. There was plenty of time between fights to get food, use the facilities and so on. It was not one death fight after another in rapid succession and not every fight was to the death.

In total, there would only be 20 to 25 gladiator fights in an afternoon. Usually.

Most games were smaller affairs, but during massive celebrations held by the emperors, they could get huge. Really huge. To celebrate Trajan’s triumph over what would become Romania, he had a four month celebration where 9,000 people and 11,000 animals were killed for the crowd’s enjoyment. That’s about 75 people and 91 animals a day. Some of the individual spectacles from the emperor could get really, really huge too. In 52 AD, Emperor Claudius put on a show on a lake outside Rome, brought out 19,000 captured soldiers, put them on boats and surrounded the lake with artillery. He then told them to kill each other or he sink himself.

In another instance, a general brought 140 elephants to be slaughtered. That’s an entire herd! That he captured them alive is amazing, and 140 of them is just an astounding number for animals that large. For the natural history and extermination parts of the games, the hunting became so intense that over half a dozen species were made extinct locally or went extinct outright. The Atlas Bear and North African Elephant are gone. The Auroch, ancestor to the modern cow in the west, became critically endangered due to the games, dying out in the 1600s. Lions, cheetahs, leopards, hippos, tigers – pretty much anything that could be dangerous to man was brought to the arena to be slaughtered. It was literal pest control for sport.

Not all animals survived the trip, or even arrived in full health. Seeing the tiger leap out, healthy and full of vinegar as seen in the movie Gladiator, would be rare or outright improbable.

Furthermore animals don’t just attack humans without reason, especially if they are in poor health. There is one account of a martyr who had to grab a lion’s head to make sure it killed him. All it was doing otherwise was just mauling him and leaving him alive, bleeding out on the sands.

All in all, the games were a huge operation, and a display of Roman power and control, which is exactly what Rome wanted.

The Gladiators

The TV show Spartacus: Blood and Sand presents us with what we think Gladiators look like in popular culture: bronzed adonises, pleasing to look at in physical form and truly athletic. Gladiators in truth didn’t look anything like that.

They look more like Big Van Vader than an underwear model. Strong, but with a layer of fat to protect the organs.

The common nickname for Gladiators was “The Barely Eaters” due to the diet it took to create such a build. Nonetheless they were considered the top sex symbols of their day: embodiments of virility and masculinity.

The sweat of gladiators (taken off after a rub down of olive oil) was used by Roman women as an aphrodisiac. I’m sure there are women today who would buy “Ode to LeBron James” and call it an aphrodisiac too.

Though I think he’d object to another use of gladiator fluids: a spear dipped in gladiator’s blood was used at weddings to part the bride’s hair in a way which was totally, intentionally Freudian.

But let’s get back to gladiators themselves.

Gladiators were an odd sort. For all their glamor and adoration, they were the lowest of the low socially: made up primarily of slaves, war prisoners of note, criminals who proved entertaining and so on. That said, people still volunteered for it, even up to the equestrian order (think “Landed Knights” in medieval times). Some liked it, others did not (Spartacus was one notable objector, as was the growing Christian population).

Gladiators were dehumanized almost immediately upon becoming one, swearing an oath that they were the walking dead upon entering gladiator schools, forgoing any hope of survival. Their names were shortened to first names only. In truth, these were pet names suitable to the easily disposable. To emphasize this, they were kept in chains for the first few months of training. Or maybe it was for some weird Dragonball Z style weight training. Or both.

Still, why would people volunteer for admitted ‘certain doom’? Well, there’s fame.

American and Japanese TV is ripe with “Stupid things people will do for fame”. As is YouTube. It also provided some illusory security, believe it or not. You were fed (with the aforementioned barely and a humongous, expensive feast two nights before an event), clothed, housed and so on, all on someone else’s dollar. And the whole school was full of people who would look after you, even after you died.

This brings up something of a misconception perpetuated by most Hollywood movies.

Most Gladiator fights were not to the death. The original Spartacus movie really nailed that point home in its early acts in the school. Gladiators were trained slaves, and that was an expensive endeavor in both time and flesh. It would be like slaughtering every horse which did not place above 5th in a race. An expensive hobby made impractically so. Besides, death came at the call of the crowd, and they did not like it coming unexpectedly.

A Gladiator’s life expectancy was not that good, most dying at the age of 23. But keep in mind the total average lifespan of the average Roman of similar class was roughly 25 (altered a bit by an extremely high child mortality rate). The best of the best gladiators also fought only twice a year. Chances of death were about 3 in 10. Still, off a list of 20 dead gladiators, only 3 had survived to their twelfth fight. Emperors were the ones who had the money and resources to toss around that much cash, as the earlier figures demonstrate.

Gladiators were not trained to fight well, either. They were trained spectacularly. Like pro wrestling today, it wasn’t about hurting your opponent too much, but of making a show of it, having flair and style was better than just being a killer. This extended into the costumes. At one point, the armor was silver plated. The next year, it was Gold. Silver was too blasé.

Another bit of dehumanizing occurred in with how gladiators were categorized. They were given characters of sorts, usually based on enemies or Rome fictional or real. Types were matched against each other for greatest contrast and interest. It was as much a show as a pro-wrestling match, after all.

One last thing to note, there were female gladiators, but they were apparently exceedingly rare, with less than a dozen references and only one skeleton hinting at these sorts of things. What games are hinted at are not just simple woman vs. woman. Since they were so rare, they are also referenced as fighting a man with one arm bound or (for something even rarer) a pair of dwarves. Yes, really.

I’m not sure if that ruins every dream spawned by Pam Grier in The Arena (1974), or makes them even kinkier.

The Hearts and Minds

The audience for these games is not us. They did not share our values. Ruthlessness was not something to be ashamed of in their society. If you look at the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome proper, it shows what we’d call war crimes today, being done by Romans on their enemies, to the people’s adoration.

Another example is the “Rape of the Sabine Women”, a foundational myth of Rome where the survivors of the losing side of Troy sack the neighboring town of Sabine and rape its women. The women then willingly submit to the assailants and call them ‘husbands’.

No, really.

Bet you never heard about that one in high school mythology classes.

Pity and compassion were not Roman values. In fact, they regarded compassion as a moral defect. It was one thing to show clemency, which was guided by reason (which they liked) and political necessity (which you had to put up with), but compassion was produced by emotions (which they did not like). Of the films regarding Rome and the games, only Spartacus comes close to portraying this attitude in any palpable fashion.

Another thing to note is that death was everywhere. Half of those born were dead by the age of five. A third of those survived to 20. Death by violence or disease was everywhere, numbing the Romans to death in general.

Strength, power and displays of that power were seen as virtuous, as well as punishment of those deemed ‘wicked’ by society. Ensuring that they suffer for their crimes was considered a good thing as well. They feared extended peacetime and did their best to uphold the strong image and show it to all. The “decadence” of civility was cured by the brutality and bloodshed of the executions and ‘games’ in the arena. This is an odd disconnect, especially since most movies about ancient Rome and things that follow it up show decadence as the cause of the games. It’s not wrong, mind you, but the Romans simply did not see it that way.

The games themselves were something unique for the Romans. Though they began as funeral rights (buying slaves to fight to the death so that the deceased noble could have help in the afterlife), it evolved into something much more. For the people, it was about the spectacle of grace, endurance, resistance to pain, courage and steadfastness. Also, it was a display of a peculiar Roman virtue: the willingness to die when conquered. It taught them how to live, how to die and how to bring glory to Rome.

It was a mark of being Roman to enjoy the games. In the second century, King Antiochus IV Epiphanies of Syria wanted to emulate everything Roman, and the games were part of that. However, his people were not Roman and did not exactly take to it right away. In fact, they were appalled by the deaths. They protested the brutality of it. But he preserved, doing next games with no deaths to the crowd’s acceptance, and then little by little they were acclimated to the brutality.

That’s not to say Roman’s always lapped death up. Like any audience, new and surprising things were called for. This went from simple ornate armors (like a year of Silver armor, then a year of gold); other times condemned criminals were given ‘roles of a life time’. They were forced to put on plays (actors were about as low as slaves were) and when their character died, they were killed as the script called for it. If you’ve ever read ancient myths, you know how bad that can get. But the worst of it, which I was unfortunately unable to verify, can be summed up as “bestiality snuff performances”.

It’s just the tip of the iceberg of “Why not all aspects of the amphitheater have not been put to film yet”. Death is okay to film, but you screw one goat . . .

Politics

The games themselves were political from the get-go. The first ones were put on by politicians, and it became tradition for them to put them on to garner favor with the mob. But it’s not like some carnival barker or pro-wrestling minstrel show as is often portrayed in movies. Instead, it was a solemn, state occasion (with cheers and applause of course), like a church mass or inauguration. As such, the state controlled what happened within. Death happened in the arena primarily at the request of the show runners, who listened primarily to the audience. When the Republic became an empire, it was the only place where the people’s voice could still be heard.

It told the populace a few more things the state wanted them to know. One of the most important was “This is what we do to people we don’t like.” Most of the deaths in the amphitheater were not trained gladiators, as we’ve gone over already. Still, it’s important to remember just how low the people thrown into the Amphitheater were. This is most likely why it was such a scandal when some of the more insane Emperors went down there to get some of the adoration. They tended to be assassinated rather quickly.

The whole thing was part of the whole “Bread and Circuses” guide to politics Rome used. The poor believed that the wealthy had a duty to keep them entertained.

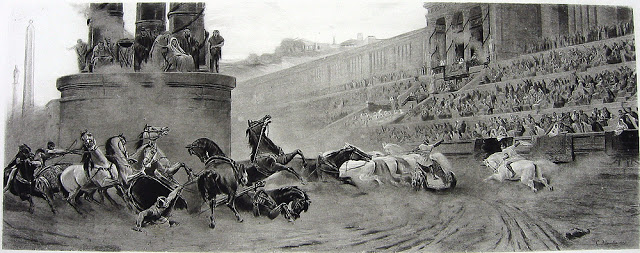

Makes some sort of sense for Rome. A million people lived in Rome itself, many of whom had nothing and basically lived off the state. Nothing to do, nothing to survive on, bread and circuses were a way of life. Politicians believed that it kept Rome from “exploding” into violence and chaos. Incidentally, the Circus (chariot races) were always more popular than the Gladiators. Still, the homes of the rich and senators had mosaics put up for games they had paid for.

The arena itself was an inversion of the Roman world view. They saw Rome as an island of civilization surrounded by barbarians. The arena inverted that and put that barbarity directly under the control of the Roman state. This thematic principle was exploited beautifully in the Codex Alera series by Jim Butcher. Even with the ‘barbarians’ made into super-human dog-men, Neanderthal-elves and yeti with ice powers, Butcher still points out that, like in the real world, the ‘barbarians’ were not as uncivilized as the Romans believed.

The End

The Roman games ended with a long whimper rather than a spectacle bang. It began with Christianity’s growth. It held compassion and mercy to be good things, which was very un-Roman. The power of the devoted in face of death, usually in the Arena, did more to promote the religion than it did to quell it. Based solely on how they handled themselves in the face of death.

Even after Rome converted, they still held the games. They just didn’t kill other Christians, which sadly proved to be the Christian attitude for thousands of years afterwards. But before and after, Christian critics spoke out against the games:

“This cruel and bloodthirsty sport, the wickedness of the fighting.”

– St. Augustine (4th Century)

Rome’s gradual decline also signaled the games’ fall. Whenever a territory fell into “barbarian” hands, the games just up and ended. Many people, by then, saw it as a relief.

“We Romans oppress each other. A man cannot be safe unless he is wicked. So many people, well-educated and from good families, flee to our enemies. They would rather endure a foreign civilization among barbarians, than cruel injustice among the Romans.”

– Salvian (5th Century)

But here we are, thousands of years later, and people still talk about them and tell stories of them.

The idea fascinates us, or we are fearful of the idea that human beings ever had a system that cruel. Though the perfect storm of politics and society may never happen again, it’s no good to be lax on such things. It is how Mixed Martial Arts went from cries of “Modern Day Gladiator Games” to one of the better regulated and safer combat sports out there.

But in the land of fiction, we’re always just a few steps away from the games, be it a future dystopia, the bored rich and powerful, or a lone madman with a fetish.

To Be Continued…