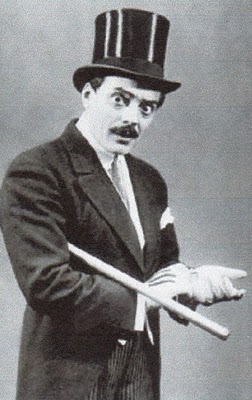

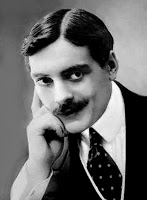

Before Charlie Chaplin, before Buster Keaton and before Harold Lloyd, there was Max Linder.

Chaplin called him his “professor”, and Linder’s comedies contain sequences that would later influence future generations of comedians from the Marx Bros. to Rowan Atkinson.

Linder was also perhaps cinema’s first comic genius, writing and directing his films in addition to performing in them.

In naming the major figures in the history of screen comedy, Linder is too frequently overlooked, or written off as just a figure from the early period. But his career actually spanned from 1905 (when he got his start at the Pathe company in France), through the 1910s (during which he worked briefly for the Essanay company in the United States), before finally returning to France in the 1920s.

In naming the major figures in the history of screen comedy, Linder is too frequently overlooked, or written off as just a figure from the early period. But his career actually spanned from 1905 (when he got his start at the Pathe company in France), through the 1910s (during which he worked briefly for the Essanay company in the United States), before finally returning to France in the 1920s.

The story of this pioneer movie comedian’s career is interesting as a parallel to the more well-remembered comedians of the silent era.

Born in France in 1883, Max Linder’s background was on the stage.

Though Linder was trained in drama, he also performed comedy, and developed his skills in theater. At this time, before film, before radio, and before other forms of recorded media, the stage was the only place for a comedian to learn the trade. Because of the rigorous demands of live performance schedules, it allowed these comedians to sharpen their skills every night before an audience, learning what bits of business worked and which didn’t.

It’s no surprise, then, that Linder – like so many of his fellow comedians later on – was able to effortlessly make the transition into film comedy.

The heyday of Linder’s screen career was his time with the Pathe studio in France. His character of “Max” was a precursor to the kind of genteel characters that comics like Harold Lloyd and Charley Chase would later specialize in. Sporting a dapper appearance, Linder didn’t look inherently “funny”. His comedy arose from the situations in which his character found himself. Frequently using farcical plot devices, Linder’s films derive their laughs from his character’s reactions to the situations around him.

In “Troubles of a Grasswidower” (1912), for example, Max plays a henpecked husband whose wife leaves him. The comedy comes from Max’s attempts to cook for himself, which he does in a hilariously inept sequence that recalls Buster Keaton’s attempt to cook a meal for the first time in THE NAVIGATOR (1924). This is just one of the examples of Linder’s influence on later comedians.

“Max Takes a Picture” (1913) is another typical effort. Here, Max visits a beach, and tries to snap a photo of a girl swimming in the surf. She swims out further and further to escape his camera, and eventually Max panics when he believes he has caused her to drown by swimming out too far. The girl makes a surprise appearance in the end, getting the last laugh on Max. This kind of situational comedy was Linder’s specialty. It’s interesting to contrast it with the faster-paced, slapstick-driven farce of the Keystone company that was emerging in the US at the same time.

Whereas the Keystone comedies relied heavily on editing, mugging, and knockabout slapstick, Linder’s films are situational, preferring to let the camera linger on the performers, giving them breathing room to perform their comic business, and to allow the comedy to build within the scene.

According to Linder’s biography in World Film Directors, Vol. I, 1890-1945 (edited by John Wakeman), he served as a dispatch driver during the first World War, as he was unfit for military service.

However, this was followed by an offer to come to the US and make films for the Essanay company, which had previously produced the Chaplin comedies. Linder’s Essanay films were not as successful as they had hoped, however, and further efforts at making films in the US never really caught on, though his feature-length comedy SEVEN YEARS BAD LUCK (1921) remains an interesting work.

It is perhaps most famous for its “mirror routine”, in which one of Max’s servants (to whom he bears a strong resemblance) breaks a mirror, and must try to fool Max by matching his every move perfectly.

This routine, of course, was later famously used by the Marx Bros. in DUCK SOUP (1933).

SEVEN YEARS BAD LUCK represents the difficulty that Linder had at this point in making a really unique comedy. It’s a film driven mostly by its gags and situations rather than character. Compared to the films of Chaplin, Keaton and Lloyd – all of whom had perfected and fully developed their screen characters by this point – Max Linder’s film lacks the kind of strong comic persona at the center of its gags, which are still quite clever nonetheless.

Another film from this period, BE MY WIFE (also 1921) contains a sequence in which Linder must convince a group of people standing outside a room that he is bravely struggling with and eventually beating an intruder. He cleverly suggests the presence of his opponent by “fighting” himself – staging an entire fight inside the room with just himself.

This sequence was later borrowed directly by Rowan Atkinson in JOHNNY ENGLISH (2003), when he tries to convince the crowd that he has successfully subdued the thief that has made off with the crown jewels.

Unfortunately, Linder’s story has an unhappy end.

His remaining Hollywood films were not a success, and he continued to suffer from severe depression.

After returning to France, he made a few more films, and his life ended tragically in 1925 when he and his wife died in a joint suicide.

After returning to France, he made a few more films, and his life ended tragically in 1925 when he and his wife died in a joint suicide.

While Linder’s life was cut short at a tragically young age, his work continues to be re-discovered, especially thanks to the efforts of his daughter, who released a compilation of his work.

His influence runs deep through screen comedy right up to the present day.

And thankfully, we still have many of his brilliant films in which he was immortalized as one of screen comedy’s first geniuses.