“To deny our own impulses, is to deny that which makes us human.”

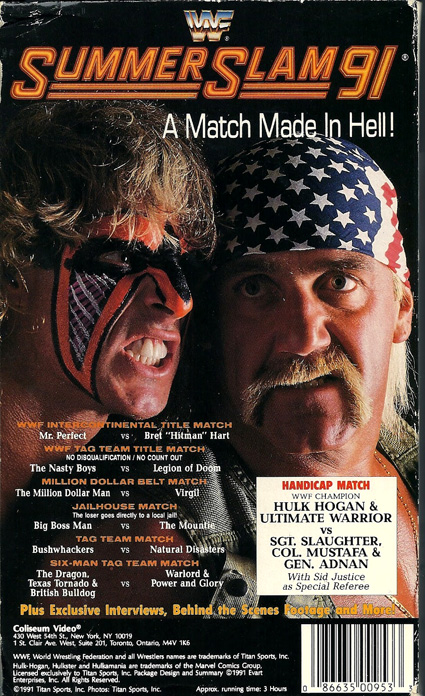

On August 27, 1991, my brother and I watched the World Wrestling Federation’s SummerSlam 1991 pay-per-view.

The event actually aired the previous night, but a friend of a friend had taped it for us, so we watched it late. Of course, this was before the World Wide Web and rampant spoilers, so we still didn’t know any of the outcomes. We only knew we were looking forward to an amazing card, toplined by the big main event of Hulk Hogan and Ultimate Warrior against Sgt. Slaughter and his Triangle of Terror.

What we didn’t expect was Mr. Perfect’s Intercontinental title defense against Bret “Hitman” Hart stealing the show. And neither of us could have expected how well it would hold up even now. It’s routinely cited as one of the best matches ever. It’s one of my favorites of all time, if not the one favorite. The match catapulted Bret toward superstardom and forced us to accept and embrace a faster, more physical style of wrestling, one that centered less on lumbering big men and more on smaller technical workers. If you were watching then, it was probably the same for you.

In a way, that match was a passing of the torch. “Mr. Perfect” Curt Hennig was widely regarded as a technical wizard, a former AWA World Heavyweight Champion and Tag Team Champion (with Scott Hall) who was a future lock for the WWF Championship. Injuries, however, derailed his momentum and forced him into early retirement in the summer of ’91. He came back for one last match to drop the Intercontinental Championship to another guy known for his technical skill and solid storytelling, Bret Hart.

Hart–like Hennig, the son of AWA favorite Larry “the Ax” Hennig–was a second-generation wrestler, the son of Canadian great Stu Hart. He was a product of Stu’s basement “Dungeon” and cut his teeth in the business wrestling alongside his brothers in Stu’s Stampede Wrestling promotion. The WWF came calling, and Bret joined his brother-in-law Jim “The Anvil” Neidhart to form the Hart Foundation tag team under manager Jimmy Hart (no relation). The two of them had considerable success, twice winning the WWF’s Tag Team Championships. At the end of the ’80s, however, the Federation quietly split them up into singles careers, with Bret quickly chasing the Intercontinental Title.

Which leads us to this moment, to this match, and this day sitting on the floor in my grandmother’s living room, watching a tape-delayed SummerSlam with my six-year-old brother.

Curiously enough, I don’t remember the build to this match very much. I could probably give you details about the lead-up to the handicap tag main event more easily, about how Sid Vicious came from WCW under the name Sid Justice, how he was made special guest referee of the tag match, and how everyone wondered just whose side he was on. I could tell you about the psychological war waged between the Ultimate Warrior and Jake “the Snake” Roberts.

I could even tell you about the run-up to the wedding of “Macho Man” Randy Savage and Miss Elizabeth–I could even quote his stuttering, quavering rasp as he bent down on one knee in the middle of the ring, and popped the question with Mean Gene holding the microphone. Hell, I could even describe the dress Elizabeth was wearing when he proposed.

But I couldn’t really cite any details about Bret and Mr. Perfect. Bret was the number one contender for Perfect’s title, the two of them traded promos back and forth, and that was that. Certainly, Bret wasn’t the type of guy who could get anyone too excited on his own. He was kind of a terrible promo, as opposed to Hennig, who was just as proficient on the microphone as he was in the ring. What the two men shared, however, was a peerless grasp of ring psychology coupled with impeccable mat wrestling skills.

I’m not going to describe the match to you, not when you could just watch it yourself. I’m also not going to pretend to be an expert on ring psychology. I’m just a big mark who can appreciate a good match.

But it has to be noted that the match was excitingly paced, and the two competitors showed such great conditioning. Both men traded offense back and forth, and the lion’s share of the match stayed in the ring, which I liked. I enjoyed how Perfect worked the match with utter cockiness and even disdain for his opponent, and of course I loved how Bret finished the match with an amazing counter. And of course, the commentary team of Gorilla Monsoon, Bobby Heenan and Roddy Piper kept things lively, bickering back and forth over just who wanted the win more, Bret or Perfect. Bret’s family being in attendance at Madison Square Garden was also a great touch, adding pressure on Bret to win it.

I would love for this to be my lasting, most prevalent memory of Bret Hart. But it isn’t.

They say you should never meet your heroes.

I like to poo-poo that idea, because I’ve usually had pretty good luck with that. Half of the time, I kind of let out some string of half-babbled words, coherent enough to engender a sympathetic response. The other half, I tend to bring up some obscure work that a notable person might barely remember him or herself. For the most part, my celebrity interactions have been very positive.

I had every reason to believe that meeting Bret Hart would be no different an experience. It was November of 2005, and he was signing his just-released DVD at a Northeast Philadelphia Best Buy. My brother was with me, and we ended up making a new friend while in line. Once we finally got to Bret, I lost command of the English language as expected and stammered out some sort of overly reverent remark. My brother, every bit a Hitman fan as I was but not really that kind of fan, took the opportunity to ask if there was any truth to the rumors of Hart doing some work for Total Nonstop Action Wrestling. Bret not only didn’t answer, but was very curt in his dismissal.

It was the first time I’d thought of Bret as human.

—————-

I cracked that bad boy open the moment I got home. Bret Hart’s DVD is great for his fans, as it has a lot of great footage not only from his WWF and WCW years, but also a ton of Stampede Wrestling clips. That’s one benefit of WWE buying up the tape libraries of these different promotions–the footage is becoming much more readily available.

But what I really noticed for the first time is just how much Bret buys into the legend. His interviews center on one root theme, which is how much of a hero he perceives himself to be, and how the business changed for the worse when it began to court an older audience and feature edgier content. Even in the ’90s, Bret was notably critical of the WWF’s darker content, to the point where it became a part of his onscreen character.

But watching him on his DVD, or in the documentary “Hitman Hart: Wrestling with Shadows,” it’s pretty clear Bret Hart holds himself in very high regard. That’s not unusual in professional wrestling, or in any area of entertainment. That doesn’t necessarily make it okay, and it doesn’t prevent me from feeling a sense of unease.

A lot of Bret’s ’90s issues are intertwined with his feud with Shawn Michaels, a work that evolved into some very real issues that ended up changing the business of professional wrestling and kickstarting the “Attitude Era.” The irony is that Bret’s greatest defeat is the spark that killed the WWF he knew and loved. This enmity is evident just through a glance at the DVD lineup. In all the extra matches, Shawn Michaels shows up only once, in a tag match between the Rockers and the Hart Foundation.

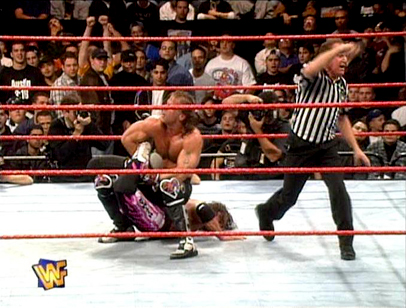

Okay, to say Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels just had “enmity” and “very real issues” is to do that entire chapter a disservice. I’m assuming you’re a wrestling fan if you’re reading this, but I should explain if you aren’t: Hart and Michaels are the key characters in what’s simply known as the Montreal Screwjob.

The short version is that Bret was headed to rival company World Championship Wrestling–not really what he wanted, but Vince McMahon actually convinced him to do it, for the money–and had to “do the job” (i.e. lose) on the way out, as he was WWF Champion. The problem was that Bret had to do that for Shawn Michaels, a man he hated, in Canada, his homeland. Bret had legitimate issues with Michaels, and didn’t want to lose to him in Canada, so he proposed a no-contest, or “smoz” finish in their Survivor Series 1997 match, then he’d drop the belt the following night on Raw before leaving the WWF. Vince agreed to this, but secretly arranged to take the belt from Bret at Survivor Series. He did this by having the referee declare Shawn the winner by submission when Michaels had Bret in his own finishing move, the Sharpshooter. (“Ring the fucking bell,” Vince shouted, unofficially signifying his own turn into the evil “Mr. McMahon” character he’d later officially adopt on television.)

There really is no short version of that story, I’m sorry.

The rest of Bret’s career–hell, his life–was colored by that incident. His time in WCW was unremarkable, as the company found new ways to squander its amazing roster of talent every week in favor of massaging Hulk Hogan’s ego. It’s telling when a wrestler of Bret’s caliber has his most high-profile feud with Mad TV‘s Will Sasso.

Shawn shot to new heights as champion at the dawn of WWF’s most profitable period. His D-Generation X group was one of the biggest draws in wrestling, and he was having five-star cage matches with the Undertaker. A back injury forced him into early retirement (shades of Mr. Perfect), but somehow, he recovered better than expected, and four years down the line, he returned not only in good ring shape, but better than he’d ever been. (Curt Hennig returned earlier that year looking better than ever too, but he had drug problems that year that led not only to his firing but also his death; Shawn Michaels had rediscovered Christianity in the meantime and beaten his addictions.)

Bret, meanwhile, had his career cut short after a quick string of concussions beginning when Bill Goldberg kicked him in the head during a match; ironic considering Bret had never once injured an opponent. Any hope of a return was dashed when a stroke rendered him partially paralyzed for a period. He’s since regained his mobility, but a full-scale return to the ring was always out of the question. If he still held bitterness towards Michaels, he certainly had a reason.

But Bret Hart has been all too willing to hold himself up as a martyr for his own cause. The reason his matches with Shawn–some of the best and most important of his career–were excised from the DVD is because Bret curated that disc himself. He selected the matches; he chose to exclude Michaels from the package.

All of this is understandable. It’s human, but Bret Hart has held himself up as being beyond humanity for a long time. To listen to Bret Hart talk about himself is to hear him described as a worldwide hero and a champion of a purer age and aesthetic. It’s to hear him put himself over as the number one good guy of the ’90s. It’s to listen to a man mark out over himself.

Still, there’s one thing Bret Hart has had over, say, Hulk Hogan, and that’s an honesty, a willingness to be entirely, infuriatingly himself. It’s the biggest thing I learned from his autobiography, which is a fascinating read for all Hitman fans or wrestling fans in general. It’s incredibly detailed, not only about wrestling but about the Hart family as well. Bret’s portrayal of himself is almost entirely unflinching–he reveals he had a number of extramarital affairs while on the road, the sort of activity to rival Tiger Woods.

What disturbs me more than that revelation is his attempt to rationalize it and still come across as a figure beyond reproach. Bret frames it as his way of staying away from drugs, that he sought refuge in women in large part to keep away from the partying and binging that claimed many of his colleagues sooner than later in life. His honesty makes the book a fascinating read; his hypocrisy makes it unsettling.

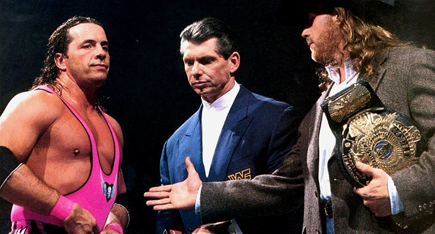

Bret Hart and Shawn Michaels did reconcile. It happened in 2010, when Bret made his first appearance on WWE Raw since 1997. The two stood in the middle of the ring, and in what both revealed to be a completely unscripted moment, settled their differences and departed as friends. That hasn’t stopped WWE from milking their past issues for added revenue, and it hasn’t stopped Bret from reliving it again, as seen in WWE’s Greatest Rivalries: Shawn Michaels vs. Bret Hart DVD. The two sat down for an interview with Jim Ross and went through their entire history together. Watching that interview, something became obvious to me. It wasn’t that Bret hadn’t gotten over Montreal–I’d understand if he never did.

No, it was obvious that Bret Hart was a huge mark for himself.

[hbk-and-bret-2010.jpg]

In Bret Hart’s mind, the business would have been just fine if he hadn’t dropped the belt to Shawn; not in Montreal, but the previous year, at Wrestlemania XII in Anaheim. There he lost it to Michaels in a thrilling 60-minute Iron Man match, a bonafide classic, arguably their best match together and one of the best matches in their respective catalogs. Hart took time off after that loss to pursue acting, but returned eight months later to engage in a bitter onscreen feud with Steve Austin. While Hart held a deep working respect for Austin offscreen (which the Texan would reciprocate), he was vocal in his displeasure over Austin’s heel character being embraced by fans. Times were changing, and Bret Hart ended up very reluctantly turning heel.

That’s another difference between Bret Hart and Hulk Hogan. Hogan saw the way the business was going and attacked his new role with gusto (although it can be argued the Hollywood Hogan character was closer to his true nature). Bret Hart, on the other hand, never really changed his character. All he did was tell the American wrestling fans what he felt about them. This led to an unusual development wherein he was regarded as a face everywhere else in the world, especially in Canada where he and his new Hart Foundation received a hero’s welcome. But it still came across as him telling the fans and the new “attitude” in wrestling to get off his lawn.

—————

Not long ago, I wrote here about Hulk Hogan, about my displeasure at the direction his career has taken. Once, he was one of my heroes, but now, he’s a guy opening a “breastaurant” and tweeting photos of his daughter’s legs. I can at least take solace that Bret Hart will likely never do either of those things, or just about anything Hogan has done. He’s managed his money well enough, and has enjoyed a well-deserved reputation as arguably the best technical wrestler of his, or any era.

And yet Bret Hart seems like more of a cautionary tale than anything else. We talk about guys like Hulk Hogan who don’t want to give up their spot at the top, but then there are guys like Bruno Sammartino and Bret Hart who try to keep the business from changing, who ignore the fact that the audiences will want something different. They ignore the “professional” part of professional wrestling, and forget that it’s a business.

Bret Hart’s most defining moments are probably his last two title matches with Shawn Michaels. Along with the emergence of Extreme Championship Wrestling, the explosion of the nWo in WCW, and the rise of “Stone Cold” Steve Austin in the WWF, those matches are key to understanding the ’90s in wrestling.

However, my favorite Bret Hart moment is still his title match with Mr. Perfect at the dawn of the decade. That, to me, is the moment that set all of that in motion. Had Perfect been able to stay healthy, he might not have dropped the belt, or he might have gone on to challenge Hulk Hogan for the top championship. But it didn’t happen that way, and Bret went on to have the career Curt Hennig might have had. In doing so, he showed a generation that it was possible to get over purely by working hard in the ring. But more importantly, he didn’t do business the way Hennig would have. He bucked and struggled where Hennig might have rolled with the tide.

Bret believed he was the best there is, the best there was, the best there ever would be, as a wrestler and as a hero. But he was half right. If anything, he was as human as the rest of us.