|

| by Benjamin C. G. Jones |

Say the titles out loud.

Superman: Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?

Batman: Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?

Similar, are they not? Parallel, in fact, and each is based on the concept of the “last” story of its respective hero.

Yet to read the two stories, one after the other, is to encounter a world of differences.

The endings began with Crisis on Infinite Earths, the landmark maxi-series meant to integrate all the worlds of the DC Comics multiverse into one consistent universe.

The “consistent” part never quite worked out, but the old multiverse did end, not to be replaced for about twenty years.

And since all of the company’s superhero titles were, in theory, starting fresh, many familiar characters saw their stories end, even as many of those characters were meant to continue in a very similar form.

One such character was the Superman of Earth-1, the one who had essentially been THE Superman since sometime in the 1950s. As definitive as this Man of Steel might be for fans casual and otherwise, he was set to be retired after the Crisis so that John Byrne could introduce a revamped Superman. Since the Superman of the Silver Age would be gone from the spotlight soon, it was left only to give him an epic sendoff.

Writer Alan Moore and artist Curt Swan were brought aboard for this task, Swan being a Superman artist of several decades’ standing, Moore the attention-grabbing author behind the rejuvenated Swamp Thing and the soon-to-publish Watchmen.

Thus, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?

Moore and Swan begin by planting us in a frame story set in the future. This is a vision of the future that was itself coming to an end in the eighties, the open collars of disco joined to the rounded décor of Flash Gordon, not a whiff of cyberpunk anywhere. In this gleaming Metropolis of The Future is a memorial statue dedicated to no one else but the Man of Steel.

Boyish reporter Tim Crane passes the shrine in order to speak to Mrs. Lois Elliott, nee Lane.

The tale that follows, the story that Lois tells Crane and us, relates not only why Superman isn’t here any longer, but why there no longer can be a Superman.

Before he dies, his world dies. This passing away starts in very literal fashion with the body of poor Pete Ross being shipped to The Daily Planet offices, Superman’s secret keeper already having breathed his last before we even see him.

This might be the right time to point out that Alan Moore is not the Doctor, and as such he loves endings. Or at least he loves the idea of finality. There’s a telling quote from Moore’s introduction to The Dark Knight Returns, Frank Miller’s famed saga of an aged Batman:

“All of our best and oldest legends recognize that time passes and that people grow old and die. The legend of Robin Hood would not be complete without the final blind arrow shot to determine the place of his grave.”

This story gives us Superman’s final blind arrow shot.

He loses his secret identity, no longer having the comforting and humdrum Clark Kent to retreat to. Friends sacrifice themselves, including Lana Lang, Jimmy Olsen, and his faithful dog Krypto. His oldest enemy Lex Luthor comes to a bad end as well, making way for someone infinitely worse.

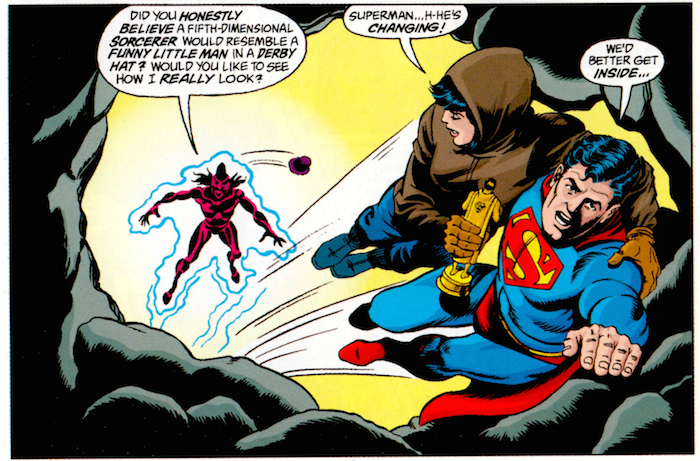

And that someone worse turns out to be Mr. Mxyzptlk.

The revelation that Mr. Mxyzptlk is behind all of Superman’s recent troubles is the final straw. The impish Mr. Mxyzptlk was always his most powerful foe in theory, given his reality warping powers, but one of the most harmless in practice. But in truth he was never a benignly silly sci-fi leprechaun, but rather a fearsome multidimensional destroyer. Faced with power this great, Superman sees no choice but to destroy Mxyzptlk.

And this is the point where there can no longer be a Superman. He walks into a vault filled with gold kryptonite and says goodbye. As Lois says, “I never saw Superman again.”

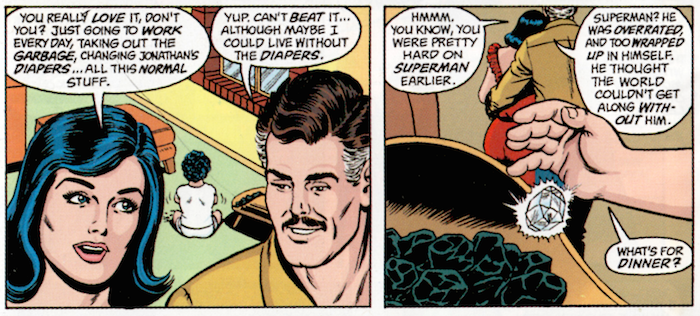

There is a final twist. The man we knew as Kal-El/Clark Kent/Superman did survive, now living under the name “Jordan Elliott” (a nod to, Jor-El, his Kryptonian father). He no longer has his powers, and more importantly he no longer carries the burden of being “Superman.”

At the happiest ending Moore could give him, he’s an ordinary man with a loving wife and an unusually strong baby son. It’s the joy of finally letting go.

Moore and Swan brought to a climax the story of Superman as nearly everyone had known him.

Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader? grew out of slightly different conditions.

The two-part story came as the denouement of Final Crisis, another epic DC crossover story, this one written by Grant Morrison. Unlike Crisis on Infinite Earths, Final Crisis did not in and of itself create any major revisions in the DC continuity.

One thing it did do was kill off Batman, who had in many ways displaced Superman as DC’s figurehead. No one ever expected the Dark Knight’s death at the hands of universal tyrant Darkseid to stick.

It did, however, provide an opportunity to explore what Batman’s life had meant, and what his death would mean. And since nothing succeeds like success, they looked back at the old Last Superman Story and thought, “Why not?”

No doubt the company would have been thrilled to have Moore write this story as well.

Unfortunately by 2009 DC and Moore had long burnt any bridges connecting them. One talent who was available was Neil Gaiman, another British writer, and one personally tutored by Moore. It would be wrong to reduce Gaiman to the “next best thing,” though. He had penned all 75 issues of The Sandman, which has few challengers as the most versatile and sophisticated book ever published by a mainstream comics company.

Along with other comics, he’d gone on to become a bestselling novelist as well. Safe to say that his credentials were in order.

Gaiman and Kubert had a different assignment with Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader? In the near quarter-century since the Crisis, Batman had already experienced a couple of reboots, as well as stories in different media and “Elseworlds” stories in different realities. There was no one universal version of Batman to end or honor.

The story acknowledges this multiplicity and even embraces it, in the visual shifts and the variances between various eulogies. This isn’t an endpoint, it’s a point on a cycle.

The opening panels place us somewhere other than the everyday, even the everyday of the DC Universe. Right off we see zeppelins—irresistibly retro technology—flying over a dusty deco Gotham as antique roadsters flow into and out of the city.

A typewriter billboard coaxes, “Don’t type it, finger it,” in homage to Batman’s unofficial co-creator Bill Finger. To any with eyes to see it’s obvious that we’re in the past. A past that never existed, perhaps, but how could that make it any less compelling?

A cat-headed convertible rolls through the city streets. Behind the wheel, of course, is Selina Kyle. She is the picture perfect noir femme fatale, the spitting image of Ava Gardner in Robert Siodmak’s The Killers. Her story about Batman is one of star-crossed love, of his inspiring her to try her own hand at crimefighting, of her finally letting him die as a way of saving him.

Other eulogists recall things differently.

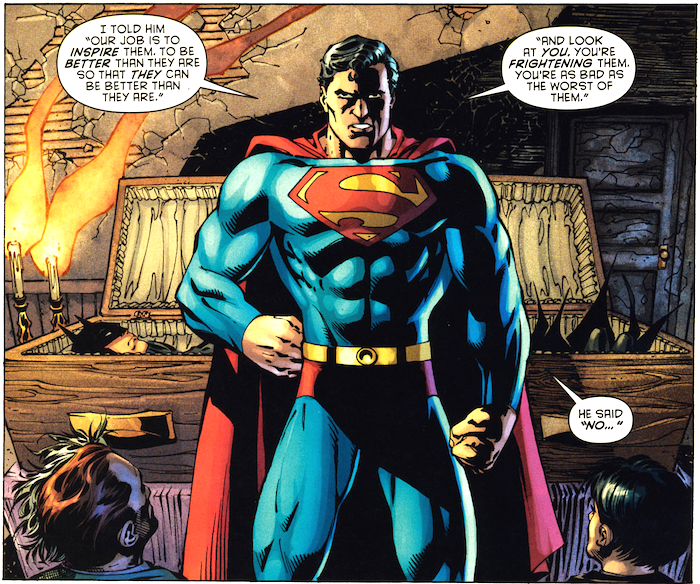

Alfred Pennyworth’s tale portrays Batman’s career as a game that became real. The Joker remembers killing Batman, but doesn’t feel the elation he expected. For Superman, Batman’s final brave act was to face the enemies who had united to kill him, in order that they not target innocents.

All the stories contradict each other, that is. And yet no one makes a big deal of the discrepancies.

There are no outraged shouts of “Liar!”

Differing in the details, and in some cases the basic outline, the stories are united by a warm and tender feeling, sad and joyous at the same time. The eulogists speak by torchlight in a backroom where boards show through broken plaster. There is beauty in decay.

Batman is there, listening to all of them. The tales don’t square with what he remembers of his own life, but they aren’t lies either. Once he’s heard enough he wanders off and passes through a simple door. On the other side he finds darkness reminiscent of both the womb and the tomb. Bathed in a light of her own amid the darkness, he finds Martha Wayne, his mother.

Being, after all, the World’s Greatest Detective, Batman can read the handwriting on the wall here. He is not dead, yet, but he’s getting there fast. The twilight wake he’s been both watching and serving as the guest of honor is his brain telling him what he needs to know before it shuts down.

Then, somewhere, the process will start again. Martha Wayne’s words are poignant and telling.

“You don’t get Heaven, or Hell. Do you know the only reward you get for being Batman? You get to be Batman. And—when you’re a child—you get a handful of years of real happiness, with your father, with me. It’s more than some people get.”

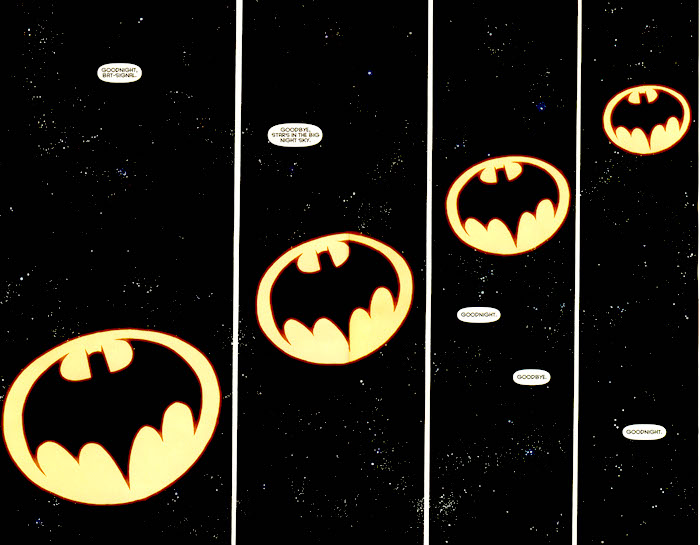

It’s a tender goodbye to everything, accompanied by a reading from Goodnight Moon.

The bat signal transforms into a pair of hands, belonging to the obstetric nurse who hands Mrs. Wayne her newborn son.

While Moore and Gaiman are friends who respect each other, their strengths and interests are starkly different.

Moore is, while he might fight against it in some of his works, a very proficient action writer. Saga of the Swamp Thing and Watchmen may traffic in messages that are subversive for the genre, but they also deliver monster-on-monster battles and a winner-take-all prison riot, respectively.

Gaiman, on the other hand, can do action when he needs to, but it’s not really where his interests lie. The author of Violent Cases and The Sandman is more invested in mysteries, Twilight Zone twists, and eerie atmosphere.

This, then, is what the difference between the two stories comes down to: for Superman, Moore writes an apocalypse. For Batman, Gaiman writes an elegy. Moore works with Swan, the artist who had defined the character since Lucy gave birth to little Ricky, the better to demonstrate the fall of the absolute Superman and his world in all its Silver Age detail.

Gaiman works with Andy Kubert, who had some experience with Batman—including a crossover with the Predator franchise—but wouldn’t be considered the definitive Batman artist even if you limit the running to those still alive in 2009. Rather he’s a very good illustrator who can adapt to old styles and make them look timeless rather than nostalgic.

Two heroes, two authors, two endings, two views of time. For Moore, time and history are linear, cause and effect cannot be reversed, and all things come to an end, good and otherwise. Gaiman takes a more Eastern, cyclical view.

Some ideas are two powerful to die out. History recurs, if not the same way every time.

While writing stories to fill similar niches, Moore and Gaiman produce narratives that differ starkly in philosophy and aesthetics.

What they share in common is that in a commercial genre, both writers pursue their personal visions.

1 Comment