the Black Lives Matter movement, my nerd-pop culture mind immediately linked to

a hulking, mistifying figure and his terroristic-revolutionary message of

tearing out society by the roots.

thought of a sentence he says as one of his faithful stays behind on a hijacked

plane about to plummet to the earth.

Hardy inexplicably chose.

racialized police violence, I often prefaced any of my social media posts

containing a story about BLM or police reform with a variation of the phrase,

“The fire rises.”

back to Los Angeles and Detroit and Philadelphia and elsewhere. There’s the fire of ever-feared black rage, the well from

which white society often attributes a stereotype of superhuman brute strength

that must be controlled by paternalist white overseers.

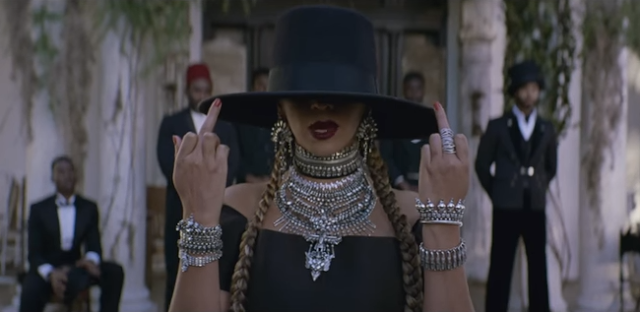

rising fire: Beyoncé’s sinking patrol car from the video for call-to-arms

“Formation,” and Kendrick Lamar’s gigantic actual bonfire blazing behind him at

the Grammy Awards last Sunday as he wailed on his informal BLM anthem

“Alright.”

follow the Hamilton cast, reminded me of my dream for an Afro-American

historical fable like Danny Boyle’s opening ceremony for the London Olympics. The

pageantry and fiery spectacle was like watching a modern-day hip-hop musical, a

bookend to Lin-Manuel Miranda’s take on the Founding Father that disrupts

historical narrative by sliding people of color, and their music, into pride of

place.

And here was Kendrick, essentially doing the same by crafting the most

audaciously fiery and critical hip-hop performance at an event that has been disrespectful

to hip-hop (no award categories until 1989) and R&B (none until 1995).

Just

two years ago, Grammy voters chose Macklemore over Kendrick for best rap album.

Even Macklemore apologized to Kendrick about his inferior album winning, as he

continues to pick at the white privilege that anoints him as “safe” in a genre

largely defined by black struggle.

Kendrick performed a Black Lives Matter anthem. (The line “And we hate po-po / Wanna kill us dead in the streets for sure” was conspicuously absent, though.) He came out in prison chains

and blues and forcefully, aggressively rapped on the rage of black strife (“You

hate me, don’t you? You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture”)

amid guitar thrash and saxophone.

Kuti-like imagery, yelling, “I’m African American, I’m African / I’m black as the moon, heritage of a small

village.” All as that gigantic bonfire raged behind him.

falls away to a single spotlight as Kendrick spat contempt at modern slavery

and the killing of Trayvon Martin: “On February 26, I lost my life, too.” The

strobes flashed as the cameras cut, an assault on the senses resembling a

psychological break or traumatic episode.

in part catalyzed the Black Lives Matter movement, I’ve written and spoken at

length about the mental state living under suffering, deprivation,

dispossession and death under systemic racism. It’s a tortuous grief that just

sits in the psyche, like a box of death, at all times. Luck, privilege and

placement on the socioeconomic ladder may make the box smaller, the lid more

closed, but the box remains.

Kendrick, you can rage and confront the pain and anger head on.

All the denigration, all the devalued

differences, all the disreputable pieces by which your entire people are

painted. You can confront internalized stereotypes and white gaze-fueled ideas

of respectability, and say, “I’m all that and more, and amazing because of it.

Fuck your expectations.”

expected to conform to a racialized idea of The Way To Behave to please white

folks, there’s a disquieting aspect to white social acceptance that too often

falls along supremacist ideas. That, to

get along, you need to not be seen as black, to be “one of the good ones” and “not

like those other black people.” To strip away your difference and play by their

rules.

inward to create some personal, political music speaking to her life and

identities as a woman. From beauty/body issues (“Pretty Hurts”) to motherhood (“Blue”)

to sex (“Partition”), jealousy (“Mine”) and the empowerment of self-regard (“Flawless”), Beyoncé went to a whole new level in a career of making music for women.

bit of her black heritage, all the parts considered unsavory and uncouth. In just

one line alone, she snatches up both “Negro” – that old-school (or outdated)

word for black Americans – and “bama,” the near-slur used to negatively

describe country black folk.

online talk among black people about “fixing” her hair. She praises “my Negro

nose with Jackson Five nostrils” and that she’ll never not be country despite

her riches. “I got hot sauce in my bag, swag.”

roles regarding sexual satisfaction and reciprocal gifts, at items of ownership

from expensive sneakers to record industry/cultural dominance. If Beyoncé’s

onstage persona is that of power, she outlines several kinds of power in “Formation.”

in the backdrop of her Southern, Louisiana heritage. She’s the girl in the wig

shop, the creole belle in her parlor, the hood chick in the El Camino sipping

on Cuervo, the round-the-way girl with her squad of girls dancing on home

movies.

brutality, linking Black Lives Matter to the 21st century’s first “they don’t

care about us” moment. In this world of “I slay” black excellence, a black boy

can dance, and the riot-gear officers put their hands up and don’t shoot.

dancers to get in formation as they twirl on them haters. Even if their Busby

Berkeley-Esther Williams production is in a derelict, empty pool.

black men out of the chain gang formation.

whether white people like it or not, understand it or not. Beyoncé will do it

at the Super Bowl halftime show with Black Panther Party backup dancers twerking

while she rocks fishnets and Michael Jackson bandoliers.

write for me, to tell my truth honestly and knowledgeably.

That to be pro-black

doesn’t mean being anti-white, to assert difference isn’t the same as being

divisive, to disrupt an inequitable situation isn’t automatically a

nullification, to assert one’s whole humanity while withstanding the fragility

of white supremacy.