|

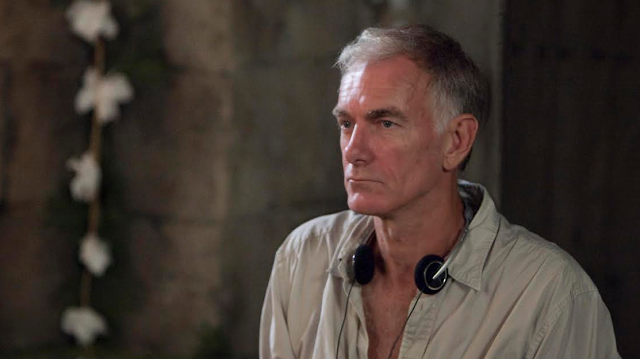

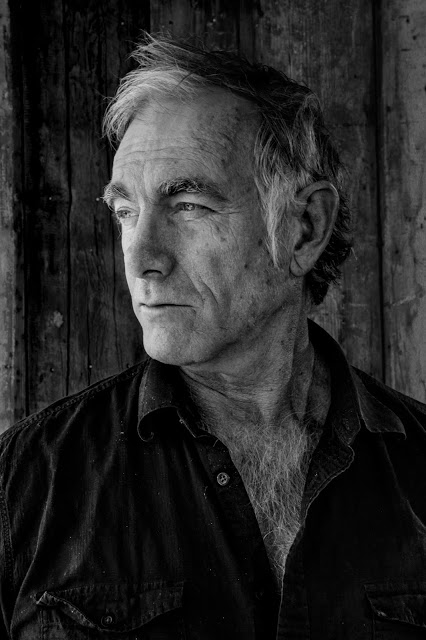

| photo by Mary Cybulski

Interview conducted by Lily and Generoso Fierro

|

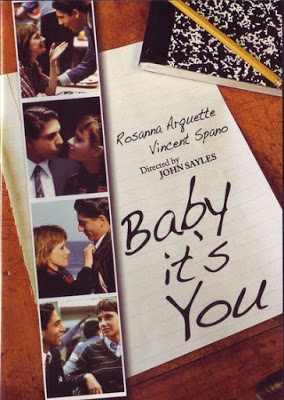

We were beyond honored to speak with legendary writer/director John Sayles on the eve before his three night career retrospective at Cinefamily in Los Angeles. “A Weekend With John Sayles” kicks off Cinefamily’s two month program entitled “Underground USA: Indie Cinema Of The 1980s,” which highlights some of the finest efforts of that era’s vibrant independent film landscape.

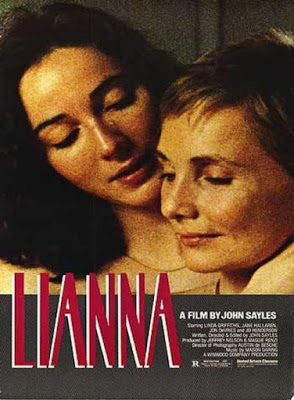

We spoke in depth with Sayles about two of his films that Cinefamily will be showing as part of the retrospective: 1983’s Baby It’s You and Lianna. We also touched on the bizarre Roman Catholic contributions to Sayles and Generoso’s education in cinema, the research methods employed when writing a script, and the challenges of updating a screenplay with Scottish director Bill Forsyth due to that director’s thick Glaswegian accent.

Generoso Fierro: Of your films that Cinefamily is showing as part of their underground films of the eighties, the film that I am most excited to see again and to your thoughts on it is Baby It’s You. I’m Italian-American and was a teenager living in South Philadelphia when the film came out, and it really resonated with me and my friends, one of whom eerily resembled the character of Shiek in the film, more than any other contemporary film at the time that dealt with young people in love because, specifically, the film addresses the issues of class and then the city during the 1960s as seen through Jill and Sheik’s relationship. In some ways the film seems like Romeo and Juliet, but Jill Rosen is never accepted completely by her Anglo college friends, and Shiek fails in Florida where he should have been accepted. What do you feel is the takeaway in terms of race and class from this film?

John Sayles: Well you know one thing that I have always felt about that movie is that people in America would like to think that we don’t have class. And, we absolutely do; it is just much more complex, and it is not as quickly defined as it is in Britain where you open your mouth and say two sentences, and they say that this person is so and so, and they went to that kind of school. And in America, class can shift around; money can change class very quickly in this country, and it takes a lot longer to change class in other countries.

What are the things that people allow to separate them, and what are the things that bring them together? And rock and roll was one of those things that brought people together. It’s a movie that is saturated with that music. You know it brought black and white kids together and Jewish and Catholic kids together. But then, there are things like education that separates people. Ethnicities can separate people, and money can separate people, so some of it was about that and some of it was about that time.

In 1966 when the film was set, you could go from high school to college and travel from the fifties to the late 1960s as far as what was cool and what was accepted and what the values were. So, for Rosanna Arquette’s Jill, it is an even bigger jump than that usually jump from high school to college because it’s this huge cultural jump from Trenton, where the drama teacher still talking about deportment and sitting like a lady, and then you go to a place like Sarah Lawrence where people are screaming and crawling on the floor, and that is theatre.

Only a few months ago, I showed Lily Baby It’s You, and a scene popped out out for both of us: the moment when Jill Rosen is shooting pool with one of her Sarah Lawrence classmates who is played by Tracy Pollan. Jill’s classmate remarks to Jill after sinking a shot that she (Pollan) will always win. Even though both women appear to be upper middle class people, that line seemed to speak volumes about the divide in their relationship in terms of Jill being Jewish and her classmate being Anglo; was this what you intended?

I think it was a little less about Jill being Jewish and more about Jill being from Trenton. That statement was more about, “This is new for you and your people, and there are things endowed at this college that were named after people in my family, and you just got here, and you are never going to quite be comfortable here.” In the finale of the movie, what’s important is that Jill gets to this point where she accepts that part of her is Trenton, and “Here’s this guy and I’m not going to hide him. And I’m going to say to all of these kids who I have been trying to act like ‘This is me; take it or leave it.’”

And that’s a big deal for people of that age to not just pretend to be what everyone wants them to be.

You also get the sense at the end of the film that even though Jill is making a statement by bringing Sheik to the dance that they are not destined to be together forever. I read that Paramount was not particularly happy with the ending of that film as it was so melancholy and asked you to change it, but you won out in the end and kept your original ending. How did that affect your relationship as far as distribution with Paramount, and is it clear that Jill and Sheik’s time together will end shortly?

They will not be together. They are definitely going in opposite directions, and they probably would have separated anyway, even if she hadn’t gone to such a classy college, but they have marked each other. They have done that thing of crossing some divide and learning about the other one being a human being, so the world in their heads is a bigger world because of that. As for the other question, it was never the ending that the fight with Paramount was over. What happened was that while we were making that movie, Fast Times At Ridgemont High and Porky’s came out, and I think that they got “high school comedy” in their heads. They had read the script, and it wasn’t a high school comedy. Jill and Sheik go off to college; it is not broad, and so they thought that in editing that they could make it into some other kind of movie, and the cut that they did didn’t test any better than my cut, so they eventually begrudgingly gave it back to me, but all their edit really did was make Sheik a lot dumber to make him more of a comedic character. So, if you think of Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, they tried to make Sheik into the kind of character that Charlie Sheen plays. Sheen plays this minor character who is kind of a thug and is played off for comedy, and that is not the story, and it is not the relationship, so it is never going to work because you didn’t have the ammunition in what we shot to make it into a high school comedy.

I think it was one of those kind of things where they had kind of backed into the movie anyway, and when they saw what they had, they thought that they could make it more commercial by cutting it into a different movie, and usually you end up with something that is neither here nor there. So, it is not as successful as what they want it to be, and it is not successful for what you want it to be. So, I actually felt good about the cut that went out, even though the studio almost forbade their publicity people to do anything for it and to dump the movie.

I heard that Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man suffered the same fate when it was released.

It is a business, after all, and they do that to a movie that they feel is a movie that won’t make any money for the studio, so why throw any more money at it? Sometimes a new regime comes in, and they simply don’t want to invest money into a film that might make their predecessor look successful.

Lily Fierro: I want to discuss Lianna next, which was released the same year as Baby It’s You. It also centers on a woman who is trying to carve out a piece of a world that is foreign to her, except that this time around at a different stage of adulthood. Were you writing that script at the same time as Baby It’s You, and were you writing them in tandem as complements to each other?

No, I actually wrote Lianna before I wrote Return of the Secaucus Seven. I was getting close to thirty, and many people I knew were breaking up, people who had been couples for a while. Some were married, and some were not, and that did not seem to be the big deal. The big deal seemed to be if they had kids or not. If they didn’t have kids, people just broke up, and if they ran into each other, they would be like “Hey, how are doing? Have a nice life.” But, if they had kids, there would be these awful custody battles, lawyers, and hard feelings.

So, I was looking for a situation where the woman was on the outside looking in, instead of the man, and there had been a couple of cases in the news where a woman who had been married with children and then got divorced took up with another woman and their ex-husbands were able to bring the family court things back in and get custody of the children.

The judge would then say that this woman is not a fit mother because this woman is now having an affair with a woman, so she’s not normal, and this will have a bad influence on the children, and they would take the children away from them, and these were women who sometimes had sole custody. Look, there is an interesting bunch of things here.

In the case of Lianna, what do you do?

She marries her college professor, so she’s never really been on the relationship market, so when you get divorced, you not only lose your children, but you also end up at the age of thirty saying, “I now have to start dating again, and oh, it is with a different sex.”

So, it seems like a volatile situation to put somebody in along with the complication of having kids.

I have always hated that in most movies, kids are like having props, so I wanted the kids to be real and have real attitudes, and their attitudes are going to change towards their mother as they get older and whomever the boyfriend or girlfriend is will be part of the equation.

I must admit that it is a surprise for me that this was written before Return Of The Secaucus Seven; did you feel that the climate in the late 1970s wasn’t right for a LGBT film? Do you feel that if it had been released around the time of the Secaucus Seven that you would’ve had huge issues getting distribution? That decade seemed to be more prime for taking risks as far as content.

No, I think that we were just lucky that we stumbled into filmmaking right about when the few independent distributors that there were were starting to have to deal with this new thing called “home video,” and so the theaters that showed non-Hollywood movies can’t just trot out 400 Blows every August 5th and play it for two weeks because people could now own that movie, so what else are we going to show now? So, there was an audience, and there were playdates for independent movies, so I wasn’t that worried about distribution; it was just that I hadn’t seen many stories like this.

I had a funny incident, I had just written a movie for John Frankenheimer called The Equals that was kind of a modern day martial arts movie, and Scott Glen was the lead on it, and I was sitting in a hotel room in Japan, having just finished writing the script, when I asked him what he was up to, and he said that he was just in a movie called Personal Best.

And I asked him, “What is Personal Best about?” and he said, “Track and field,” and left the gay woman angle out totally. Because, to his character, it was about track and field; he was the coach who had no desire to get into his players’ personal business. There just weren’t that many movie like that out then, which in some ways was kind of an advantage for our movie.

I remember the exhibitor in Atlanta telling us, “Well, I now know what the gay population of Atlanta is because they have all gone to this movie three times. It’s up to the point where men are afraid to go into the theater because they are so outnumbered, and the women have taken over the bathroom because there is always such a long line for the women’s restroom”

|

| Patrice Donnelly, Mariel Hemingway and Scott Glenn in Personal Best |

Not to digress Mr. Sayles but I would love to tell you a quick story that relates to Personal Best that details the single most embarrassing moment of my entire life. My real film education started in parochial elementary school when two nuns, Sisters Margaret and Helen, both extremely cool ladies, who every Friday night began taking me to see films at the Ritz Theater, then, one of the few arthouse cinemas in Philadelphia. On one of those Fridays, they took me to see Personal Best. Most weeks, the Sisters would vet the films using reviews, but that week they were too busy and relied on the ticket seller for a synopsis of the film, to which the woman told them “Oh, it’s about the athletes who were affected by the boycott of the 1980 Olympics that were held in Moscow.” Sister Margaret turned to Sister Helen and said, “It does have an ‘R’ rating, but that probably means that it just has some foul language and that is OK.” So, there is twelve year old Generoso, very Catholic, sandwiched between two nuns watching Mariel Hemingway engaging in lesbian sexuality…Pretty much the apex of challenging Catholic repression and guilt. So, I definitely support your claim that it was never labeled as an LGBT film.

Absolutely, they were afraid of it. When I got out college, I saw a lot of the art films I eventually liked in a Catholic nursing college in Albany, New York, in a classroom with a crucifix over the door, with a very hip Jesuit who I imagine didn’t get out of the 1980s without quitting the order, running the projector for us and watching The Silence and all of these heavy Bergman movies and things like that, so it was a familiar situation. I don’t know if they still had it when you were in school Generoso, but when I was a kid we had to stand up once a year in church and pledge that we would follow the dictates of the Legion Of Decency.

Yes, that was still briefly in place when I was in Catholic school.

So, if a movie got a “C” for “Condemned,” you weren’t allowed to go to it. We never lived near a place that would show those movies, but I would always read the literature as to see what they had condemned to see what the interesting movies might be.

I remember the film for me was Pasolini’s Canterbury Tales, which immediately grew my desire to see the film as it got the stamp of disapproval, but back in those pre-home video days, it meant having a cool adult, sneak you in under a coat.

For a final question, I know that besides the scripts that you have written and then directed yourself, you have also written many scripts over the years for other directors including the first draft of E.T., The Howling, an unproduced Jurassic Park IV, and one for one of my favorite directors of the 1980s, the Scottish director, Bill Forsyth. You wrote his 1989 crime comedy, Breaking In, which we really love and wished that more people had seen at the time. I should say at this point that my education is in criminology, and as far as films about theft and home invasions, you got the characters and situations down perfectly. What was your particular research for the film?

I read some criminology texts and some psychology books, books about the technology of breaking and entering, and memoirs of safe crackers. And I think the main thing that struck me, that gave me the original idea for the film, was the way in which there was an evolution in crime and technology.

If you saw Michael Mann’s Thief, then you saw the first time that a burning bar was used in a film. Because the technology of safes had gotten ahead of the criminals, they had to come out with new technology themselves, so I had this wonderful idea of an old safecracker who could only crack old safes. So, if you don’t keep up with technology, you have to case a place out, and if the safe is beyond your capabilities, then you are going to have to move to Canada or somewhere where you can open them the old fashioned way.

That was a project that I started as a short story but never was able to make it work as a short story and eventually made it into a script, and it just hung around for years, and it was one of those that I thought that I don’t need to direct this one myself, but I don’t want to just give it up. So, there was one producer, Harry Gittes, a friend of Jack Nicholson and that’s where the Mr. Gittes in Chinatown came from, and he kept calling me up and saying “I would really love to make this movie.” So, I asked him “Well, who is going to direct it?” and he said, “Let me think about that.” And one day he called up and said, “What about Bill Forsyth?” and I said, “You got a deal. If you get Bill Forsyth, the script is yours.”

But by this point, ten years had gone by since I had written it, so I worked with Bill to update the script a little because many of the references were too old, and I thought that he did a great job with it. I had written it with Walter Matthau in mind, so when he cast Burt Reynolds, at first I was like, “Burt Reynolds?” and then I realized that this was great for Burt Reynolds! Burt is good at comedy, and he’s not going to play like an action figure. He is going to have a chance to act a little bit, and I also thought that Casey Siemaszko did a great job too.

|

| Casey Siemaszko and Burt Reynolds in Breaking In |

Reynolds was great in the film, and I remember many critics going on and on about how Reynolds had this sweetness about him in Breaking In that was lacking in many of the films he starred in during the 1980s.

He had gotten a little wink at the audience smug in all of those Smokey and The Bandit movies, but here he couldn’t just play Burt Reynolds; he had to play a character, and he could be a very fine actor, and he really was very good at comedy.

When you are working with a director like Forsyth, who has a certain style for his dialog and characters, how much do you change your style to match theirs?

I really didn’t change the dialog much for that film. It was mostly updating things, like taking out the disco references and such things that were the norm when I originally wrote the screenplay. And then it was originally written to be in San Francisco, but Bill had scouted around, and San Francisco had gotten very expensive to shoot in, so he finally decided to shoot it in Portland.

So, then, I had to learn a little bit about Portland to see what was there that could be of use to him. He had found the skating rink, for example, so I added it into the script. Truly the hardest thing about working with Bill was his accent, which was so hard for me to understand as it was a very thick Glaswegian accent. If you have seen his films, such as Gregory’s Girl or Local Hero, that came over here, they were all post-dubbed. They got actors with less thick Scottish accents to do them when the films opened in the United States. Because with a really thick Glaswegian accent, you need subtitles.

I couldn’t agree more. Last year I reviewed Forsyth’s 1979 debut film, That Sinking Feeling, and I felt that someone should consider reissuing the film with subtitles because the accents baffle me at points.

I should say that Bill was fascinated with criminals, specifically how boring their lives are and how petty some of the stuff that they do can be. Also, he owed the studio a picture and was looking for something that had his sensibility already, and in that way, I think it was a good marriage.

|

| photo by Mary Cybulski |

For more details including screening times, visit cinefamily.org.